What Do Women in Japan Want? – And More Importantly, Why Don’t We Know this Yet?

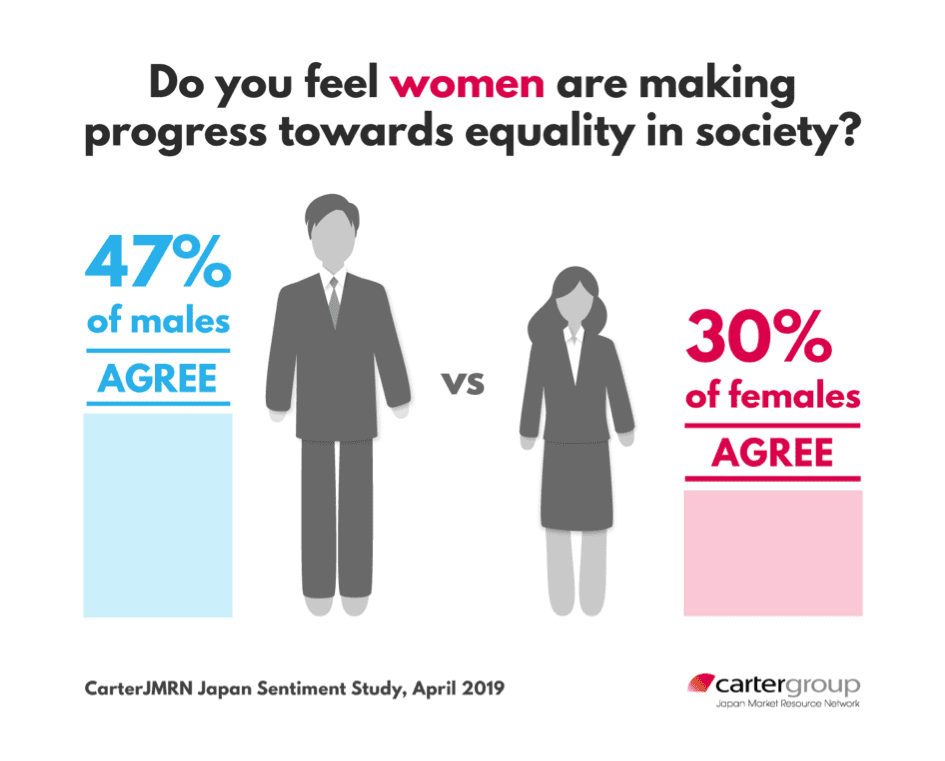

In our 2019 CarterJMRN Japan Sentiment Study, we asked 1000 men and women across all 47 prefectures whether they felt that women are making progress toward equality in society. While almost half of the men at 47% felt that this is the case, women were rather less optimistic with only 30% agreeing.

Apart from the fact that neither gender made it to 50%, what a telling result this is on the gaps of perception between the sexes in Japan!

Men think women are making progress, but women themselves don’t think so

The recent #kutoo movement has been a wakeup call for many. That the labour minister made himself into a target of derision when he asserted that forcing contemporary Japanese women to wear heels at work was ‘necessary’ and ‘reasonable’ is a definite sign of progress. However, as I’ve never really paid the topic of heels much thought until now, I have to admit the controversy has also prompted me to reflect more deeply on the gender norms taken for granted in Japan.

That hapless politician is perhaps not so out of step with much of Japanese society. Indeed, I can well imagine that many working men may feel that, given the rigid rules they also need to follow, perhaps it is only fair women should also follow the mores of the day. Given the pervasiveness of narrow gender roles in Japan, our work has also shown that some women agree there’s no need to change.

But if Japan collectively is going to choose a turning point to do things differently, and for a sustainable future… why don’t we choose the start of the Reiwa era?

The Reiwa era as a turning point

I’ve been managing in Japan for over 20 years now and our company of around 80 full-timers employs an even balance of men and women in our senior roles. I’m also proud to say that our company’s chairman is actually a chairwoman. This should have given me a perspective on what is important for women at work. But I must admit I feel the need to approach the topic with humility.

Our company is like every other in Japan. People work long hours. We are working on this problem, but it is a fairly intractable one as, not only is our business tied to the demands of our global clients who reside in different time zones, the perceived need to spend long hours at the office has deep roots in Japanese culture. This is not a cop-out on my part, but merely a recognition that if it were as easy as encouraging people to work shorter hours this problem would have been solved a long time ago.

The women in our company work every bit as hard as the men, and their contributions are just as valuable. But that means working at our firm is going to be a juggling act for many of the women with partners and families. One observation I’ve made is that most of the women I know lead, richer lives than men. By this I mean there is often more that interests, motivates, sustains, but also makes demands on women than just their careers. Of course, there are the obvious demands of child-rearing which Japanese society still places fairly and squarely on women’s shoulders. But while this is the case, I also can’t help but note women also tend to have a better sense of what’s important in their lives and are able to sense a reasonable work-life balance that works for them.

Repercussions of a rigid system

Of course, it’s not always a choice. Having been eased out of a full-time career track around the time they have children in Japan, women have built flourishing, meaningful lives filled with family, friends, community work and hobbies, but alas, often not careers, as the system has only allowed them to express their potential in other ways.

On the flipside, men in the land of karoushi, inadequate sleep, and mandatory overtime, are generally obsessively and rigidly committed to the job. This often leads to estranged husbands and fathers, high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, and a sense of being trapped, demonstrated in part by Japan’s relatively high suicide rates.

Given the extreme pressures placed upon them in traditional working roles, it’s not so surprising that some Japanese men seem to resent the more ‘exciting’ lives that women lead and have suggested to me that women therefore are less committed at work. This seems to be an unfortunate by-product of the social restraints they feel and neither gender profits from this.

There is no time for glass ceilings

Inclusiveness and equal pay for equal work as a non-negotiable goes without saying. I’ve no time and certainly no economic incentive for glass ceilings. But, equally, I wonder if our goal of equality may be better realized by re-framing the problem to create equal flexibility for men as well as women. We need to change the workplace system as a whole in a way that benefits both genders. In other words, it’s critical to consider the idea that the restrictions and expectations placed on women’s roles are the flipside of those placed on men.

So when creating an inclusive workplace, we should not only be asking what women want but what do we all really want, moving forward in society? Surely it’s a more flexible, creative, open and respectful working culture where we all have the opportunity to benefit from the talents and experiences we can cultivate outside of work. This goes for men as well as women. When women benefit, so do men.

Looking north, I see: It doesn’t have to be that way

A change where a balanced life is possible for both genders would benefit Japanese society as a whole. And for that, both men and women must be extended the same responsibilities and freedoms. If you think that is not possible, just look in the direction of northern Europe.

Denmark has been leading the OECD Better Living Index year over year. And the way they treat the issue of family and work seems to be central to this. Only 2.2% of Danes complain about long working hours. Sixty percent of Danish with children say they have no or few problems to balance family and work. Interestingly, a 37-hour work week seems perfectly adequate for them, as they are also one of the most productive countries on earth, and people generally leave the office around 4pm to pick up their kids, have dinner with their family or to just enjoy their lives. Eighty percent of women with a child of 15 years or younger are employed– most of them fulltime. The result: Danes of all genders seem to be a happy bunch, as the country is also leading the world happiness study.

Could the Scandinavian model that is so often praised also work in Japan? Or am I being too idealistic?

Before jumping to conclusions, if you’re a woman in Japan, please let me ask you: How do you think it should be? Let’s have this question spark an open dialogue in our own workplaces, and in society at large. Men in management roles also need to speak much more openly, collaboratively and more often with the women in their organisations – and I’m looking forward to doing a much better job of that. While we’re at it, perhaps we should also be making the time to ask men what they really want. It’s only by men and women working together on the problem that we can make meaningful progress to a more reasonable, productive and happy society for all.